Bird of the Month: Northern Shrike

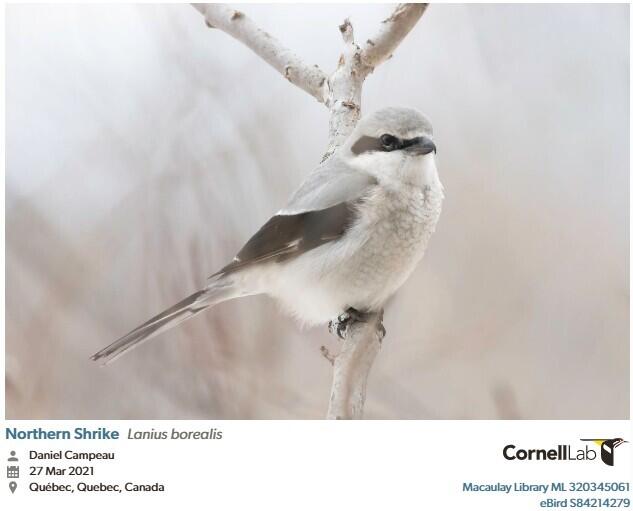

January in Colorado often brings cold mornings, quiet landscapes, and subtle flashes of life that remind us that nature never fully sleeps in winter. Among the most fascinating winter visitors to northern states and mountain regions is the Northern Shrike, Lanius borealis. At first glance, the Northern Shrike looks like a typical songbird. It measures under ten inches long, sports soft gray plumage with delicate patterns, and perches with the calm demeanor of a bird that might feed on seeds or berries. But beneath this gentle appearance lies a fierce and highly skilled predator.

Northern Shrikes belong to the family Laniidae, a group often referred to as "butcher birds" due to their remarkable hunting habits. Unlike most songbirds, shrikes are carnivorous hunters that capture prey that includes insects, small mammals, and even other birds. Their hooked bills resemble those of small raptors and give them the tools needed to tackle prey larger than one might expect from a bird of their size. The Northern Shrike is the only shrike species expected in Colorado during the colder months and is known for arriving quietly and blending seamlessly into the winter palette of the open landscape.

We'll explore the fascinating world of the Northern Shrike; its natural history, preferred habitat, hunting style, breeding cycle, and the remarkable adaptations that make it successful during the harshest times of year. We will also explore what birdwatchers can look for when hoping to spot this elusive species, along with conservation considerations and what the future may hold for these captivating birds. The Northern Shrike is a species that rewards patience, curiosity, and a love of winter birding, and January is the perfect month to highlight its presence and celebrate its role in the cold-weather ecosystem.

Basic Information

The Northern Shrike is a medium-sized passerine, measuring approximately nine to ten inches in length. It has a wingspan of around twelve inches and weighs about two ounces. Its coloration is primarily gray on the back and head, with a lighter, almost white underside. One of its most distinguishing features is the bold black mask that runs through the eye, giving it a sharp and alert expression. The wings and tail are patterned with black and white, adding contrast to an otherwise soft palette.

Juvenile Northern Shrikes are buffy and faintly barred, lacking the sharp crispness of the adult plumage. Over time, they molt into the classic adult pattern that most birders recognize. Their bill is hooked at the tip and strong for their size, allowing them to dispatch prey effectively. Their legs and feet are relatively slender compared to raptors but still strong enough to help them capture and hold prey before using their bills.

Northern Shrikes are often compared to their close relative, the Loggerhead Shrike, which visits Colorado during warmer months. The two can be tricky to tell apart, especially at a distance. Northern Shrikes are slightly larger, have a thinner mask pattern that does not extend above the eye, and tend to show faint barring on the underside during their first winter. Their general demeanor is also somewhat different. Northern Shrikes often move with a lighter, more open-country energy, while Loggerheads prefer warmer landscapes with brush and scattered trees.

The Northern Shrike is diurnal and spends winter days perched conspicuously on high vantage points such as snag tops, fence posts, shrubs, and the tops of small trees. From these perches, they scan the landscape for movement and opportunities to hunt. They are alert and quick to flee if they sense a threat, which contributes to their reputation as difficult birds to photograph or observe for long periods. Despite this, they are not shy in their hunting style. When the opportunity arises, a Northern Shrike moves fast and with great precision.

Habitat

During winter, Northern Shrikes inhabit open country with scattered shrubs and trees. Their preferred landscapes include grasslands, sagebrush flats, tundra edges, shrub steppe, agricultural fields, and riparian corridors where willows and cottonwoods offer both cover and hunting perches. In Colorado and the central United States, wintering shrikes can be found in prairies, foothills, and occasionally near open forests or rural roadsides.

Northern Shrikes breed much farther north, primarily in the boreal forests and tundra edges of Canada and Alaska. Their breeding territories are typically isolated, cold, and remote, with sparse vegetation, dense stands of black spruce, or areas of stunted trees and shrubs. These northern regions are covered in snow for much of the year, which influences the shrike’s adaptations and behavior.

In winter, shrikes migrate southward, although “migration” in their case is often subtle and irruptive. Some years bring larger winter populations to the lower 48 states, while other years see very few individuals. Their movements depend on food availability, weather severity, and breeding season success. Colorado birders often note that shrikes favor areas with a mix of open hunting grounds and scattered perches, making power lines and fence rows excellent places to search.

Food Preferences

The Northern Shrike is an adept carnivore and one of the few songbirds with a top predator role in its ecosystem. Its diet shifts slightly by season and location, but its primary foods include:

Large insects including beetles, grasshoppers, and wasps

Small mammals such as voles and mice

Small birds including sparrows, finches, and warblers

Occasionally amphibians and reptiles

In winter, berries such as mountain ash, chokecherry, and other fruiting shrubs also supplement their diet

Shrikes hunt using a combination of patience and speed. They sit on a high perch and watch for prey to move below. Once a target is detected, they swoop down in a rapid and direct flight. Their bill is not as powerful as that of a hawk, so they often use a unique technique to subdue prey. They may impale prey on thorns, barbed wire, or sharp twigs. This behavior stabilizes the prey long enough for the shrike to tear it apart with its bill. This is the behavior that earned shrikes the nickname “butcher birds.” While dramatic, this method is extremely efficient and allows the shrike to store food for later. In the cold northern landscape or during unpredictable winter days, cached prey can mean the difference between survival and hunger.

Because they are hunters, Northern Shrikes do not visit traditional feeders. Instead, their presence is tied to healthy populations of small mammals and winter birds, as well as the availability of perches and open hunting grounds. Their predation is a natural part of the ecosystem and helps keep small bird species balanced.

Mating and Courtship

Northern Shrikes form breeding territories in the far northern latitudes, usually beginning in late winter or early spring. Males typically arrive on the breeding grounds first, establishing territories by singing and defending areas that include adequate hunting perches and potential nest sites. Shrike songs are surprisingly complex. They are melodic, varied, and can include mimicry of other bird species. Their singing is especially frequent during courtship season, when males perform flights and vocal displays to attract a mate.

Courtship feeding is a common behavior. A male shrike will catch prey and present it to the female in a ritualized manner. This behavior demonstrates his ability to provide for a future family and helps strengthen the pair bond. Shrikes often remain paired for a breeding season but are not always monogamous from year to year.

Nesting and Raising Young

Once paired, the female selects the nest location, often choosing a dense spruce or willow. The nest is typically built six to ten feet off the ground, well hidden among branches. The female constructs the nest using twigs, grasses, rootlets, and feathers. The finished structure is sturdy, compact, and lined with soft materials for insulation in the cold northern climate.

The female lays four to seven eggs, which she incubates for roughly two weeks. The male brings food during this period, especially if spring temperatures remain cold. After hatching, the nestlings are altricial, which means they are blind, featherless, and completely dependent on parental care. The parents work tirelessly to feed them. Their prey during this period often includes small mammals and insects, which provide the protein needed for rapid growth.

The young fledge approximately two to three weeks after hatching. Despite leaving the nest quickly, they remain dependent on their parents for an additional two to four weeks as they hone their hunting skills. Shrikes grow quickly, and by late summer, juveniles disperse to find their own territories.

By autumn, many of these young birds begin their first migration southward. This first winter can be especially challenging, which is why sightings of juvenile Northern Shrikes in the lower 48 often hint at larger movements across the species’ range.

Spotting Northern Shrikes

Because Northern Shrikes are predators, they are not attracted to seed feeders or suet. But there are ways to increase the likelihood of spotting one during the winter months.

- Look for Northern Shrikes in open habitats with scattered shrubs or trees.

- Scan fence lines, telephone wires, and isolated perches where shrikes often sit while hunting.

- Listen for their distinctive harsh calls or melodic songs, especially in early winter.

- Watch the behavior of small birds in the area. If they suddenly flush or become agitated, a shrike may be nearby.

- Visit areas known for wintering shrikes such as prairie preserves, rural farmlands, and open foothill regions.

Landscaping Tips:

While you cannot “attract” a shrike in the traditional sense, maintaining habitat that supports small mammals and winter birds indirectly supports shrike presence. Consider planting native shrubs that produce winter berries such as chokecherry or serviceberry. These shrubs provide habitat for prey species that shrikes rely on. Keeping dead snags or perches can also create suitable lookout points that shrikes prefer during hunting.

Conservation Concerns

Northern Shrikes are not currently listed as threatened, but their populations require monitoring due to several factors.

Climate Change: Shrikes are highly dependent on cold northern ecosystems. As boreal forests respond to warming temperatures, the habitat structure that shrikes rely on may shift or shrink. Earlier springs can also affect prey availability and timing of breeding.

Habitat Loss: Development, forestry practices, and agricultural expansion in northern breeding grounds can reduce available nesting habitat. Wintering ground loss in the contiguous United States also affects their seasonal movements.

Collisions: Shrikes may collide with vehicles, windows, and power lines, especially during winter when they move frequently in search of food.

Pesticides: Reduction of insect populations through chemical use poses a risk to shrikes directly and indirectly through their prey species.

Despite these challenges, the Northern Shrike remains relatively stable. Continued monitoring, research, and conservation initiatives focused on northern ecosystems will be essential for maintaining healthy populations. Birders can support shrikes by supporting habitat conservation, practicing window strike prevention, and advocating for native landscaping that supports robust food webs.